topic

jurisdiction

downloadable assets

article

Article

AI has entered mainstream corporate practice: a 2025 McKinsey global survey finds that 88% of organisations already use AI in at least one business function.1

The question remains: Who in the organization should be responsible for governing AI use?

Hui Min Langridge: The question suggests that there might be a single person or function responsible for AI.

I already found that premise problematic when the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) had to be implemented. The mindset often was, “That is your job; you are the DPO [Data Protection Officer].” That is a very centralised approach to governance. Allocating responsibility for AI governance so narrowly can make it difficult to obtain broad stakeholder input.

For me, the better model is a hub-and-spoke structure. A specialist core group of stakeholders (CTO, Head of Cloud Operations, Legal) teams up with “AI champions” in different “spoke” business functions such as IT, HR and marketing.

The hub function demonstrates what good AI governance looks like (like setting the rules of the road and defining policies) and the champions implement this within their functions with appropriate discretion.

In other words, this model gives the functions the principles they must meet, make them responsible and accountable, but allows them the leeway to determine how best to apply those principles in their specific areas. The AI champions are people who know their business units best, after all.

The other advantage of a decentralised structure is speed: a centralised function that dictates everything becomes a gatekeeper and may slow adoption down.

Robert Kretzschmar: I would place myself more in the centralist camp. In particular, if you want to drive AI adoption in your organisation quickly, or if AI is a key part of your product offering, I would advise leaning towards a centralised model of governance.

There are a few reasons for that:

- First, you want to ensure focus on investing in AI in the right way. That was a problem in the early days of generative AI. Some companies wasted significant amounts of money as teams pursued their own initiatives independently. A centralised function can take lessons learned from one area and use them to prevent repeat mistakes in others. It can also enforce clear priorities for AI investments.

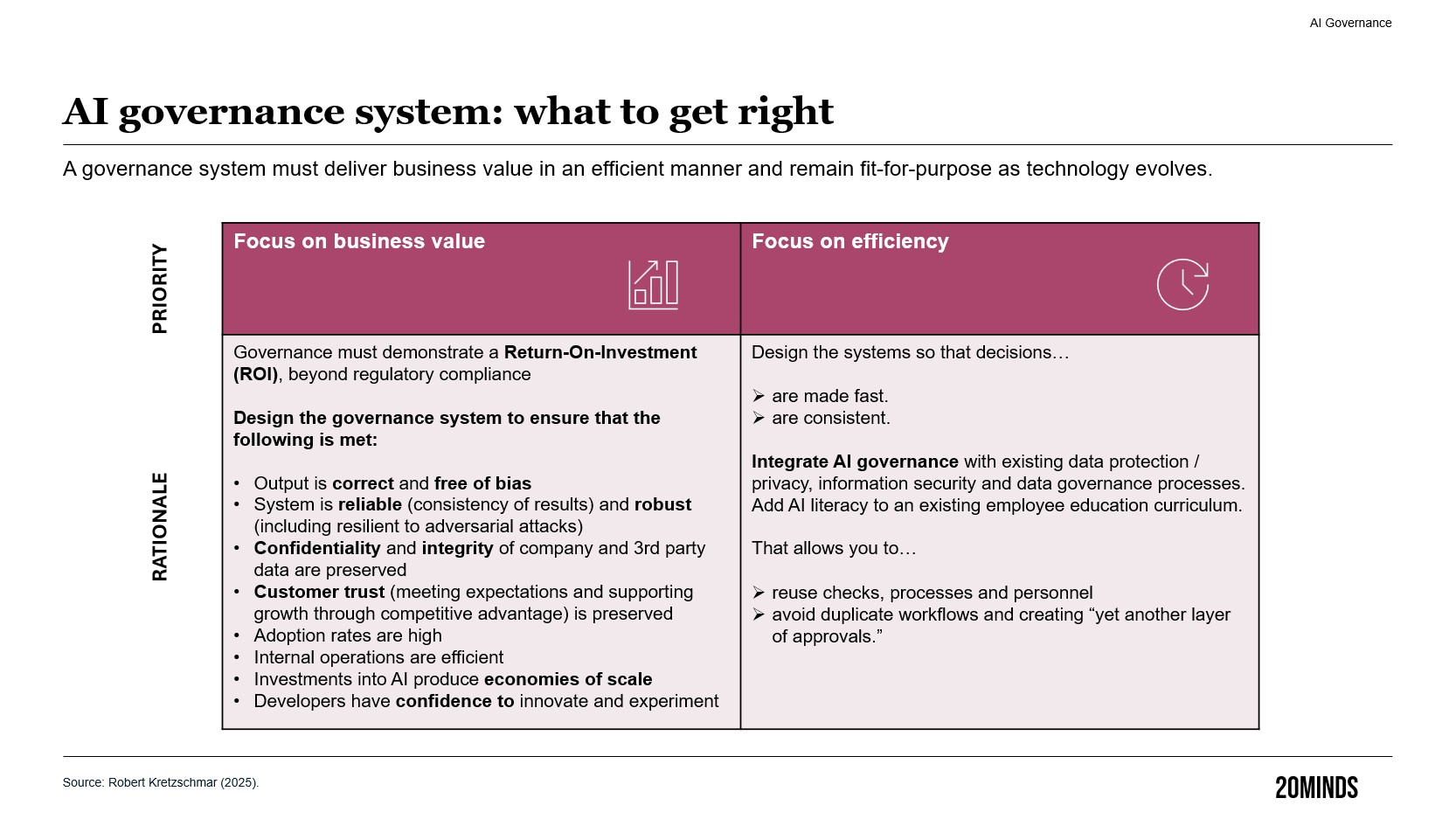

- Second, a centralised model can achieve economies of scale. A uniform platform providing (potentially on-premise) AI models and/or systems reduces the need for each team to build or procure separate solutions performing the same or similar tasks and the company to pay for multiple subscriptions. This helps coordination and improves efficiency.

- Third, you want to ensure that AI systems meet defined quality standards. These standards become detailed quickly. They cover robustness, output quality and the security of data, including confidential information.

I agree, however, that a centralised model can slow you down when oversight ossifies into red tape. So keep your decision-making committee lean and agile. Use well-designed tools to manage intake. Develop routines that speed up review and approval. Issue principled-based guidance to address function, department or region-specific topics and use cases.

Anselm Rodenhausen: Every company is different. So, I would place myself in neither the centralised nor the decentralised camp when it comes to designing a governance system. It depends on the company’s needs.

Each company has different use cases, services, customer expectations and local requirements. Risk appetite can vary widely. Even within the same industry, you may find very different cultures. Choose the system that serves your company best.

When you do that, also take into account what is already there. Some companies, especially in regulated industries, already have extensive compliance structures. In those cases, you have to ask whether it makes sense to add another centralised layer for AI. I have seen companies with so many reporting lines that an additional layer would risk paralysis. For those firms, a decentralised system that leverages existing governance may work better.

Other companies need to move quickly on AI opportunities. For them, centralising AI decision-making — and creating a dedicated structure for it — may be the better approach.

You are put in charge of developing an AI governance regime. Teams across the organisation have started buying AI tools, the CEO says, “get it under control.” What should be your priorities?

Hui Min Langridge: For me, my most immediate worry would not be the buying of AI tools. You will have some procurement controls there already that will also apply to AI. That should prevent the worst outcomes if applied correctly.

My most immediate priority would be to stem the tide of the shadow AI, that means the use of artificial intelligence tools inside an organisation without the approval, oversight and proper controls from IT, security, legal or compliance teams.

How do you get ahead of that problem quickly? You may want to consider some form of amnesty. “If you tell us, you have bought these shadow AI tools, we will not penalise you, but we need to know where they are.” Build that dialogue. Create that transparency. The last thing you want is employees doing things underground.

My second priority would be education. It helps with both shadow AI and the uncoordinated buying of AI tools. You need, at a minimum, a conversation within the firm about the use of AI — not a committee approving everything, but a discussion of the utility and risks of different AI applications.

That education piece, call it “literacy,” is key. Before investing significant time in a sophisticated governance system, raise your baseline literacy from zero to perhaps six out of ten.

Robert Kretzschmar: I fully agree. While it makes sense for the European Commission to re-think AI literacy as a legal requirement (as currently proposed in the “Digital Omnibus on AI”), literacy will remain in the best interest of companies. Probabilistic models like GenAI will continue to produce hallucinations, and literacy training helps employees critically assess outputs rather than rely on them blindly. Critical thinking should sit at the centre of any literacy programme, as it strengthens the ability to “AI-proof” roles and can support adoption, particularly among staff worried about job displacement.

Anselm Rodenhausen: I would argue that the primary task of AI governance should be to enable employees to use AI productively. It should start with the opportunities that AI creates. That is particularly important for the legal function. If all you give people are warnings — “be careful here, be careful there” — you create an atmosphere in which people think, “I am not sure I am in line with what legal said; I will not use it.”

Turn it around. Create a policy that empowers people to use AI safely. Then provide guardrails. If employees stay within those guardrails, they feel safe, the main risks are covered and they are able to use AI for the benefit of the company.

Robert Kretzschmar: I am broadly aligned. My three main points are:

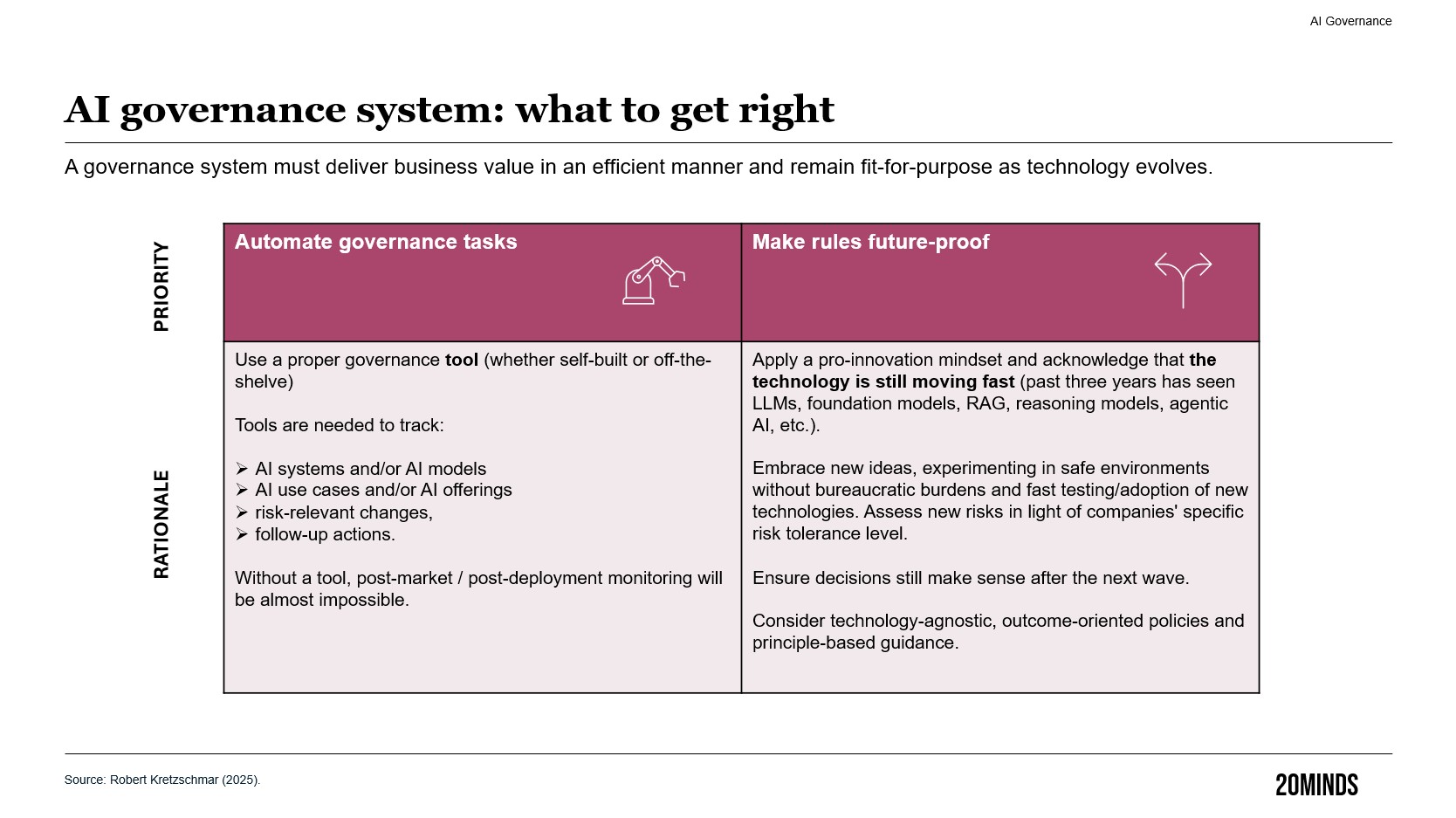

- First, build governance with a pro-innovation mindset. Governance should not feel restrictive. It should support the company’s AI strategy. Focus on awareness, literacy and adoption. You want to identify those areas where central governance really adds value, and where regulatory compliance, though important, is only one part of a much bigger picture.

- Second, focus on outcomes, not on the technology. Many use cases do not require AI. A cross-functional team should ask whether AI is truly the right path or whether rule-based automation or another approach solves the problem more effectively.

- Third, internal rules must be risk-centric and proportionate. There will always be residual risk. The company must decide what level of risk is acceptable. Lawyers tend to be risk-averse, but we need to accept the risks that come with AI use rather than attempt to eliminate them, which is impossible.

Driving AI adoption is harder than one might think. Many of us delivering AI training try to “demystify” it. Interestingly, new research suggests that keeping a bit of “magic” around AI can help employees stay curious, interested and engaged.

We thank the participants for their candid observations.

Sources

1 McKinsey & Company. The State of AI: How Organisations Are Rewiring to Capture Value. 2025. Available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/capabilities/quantumblack/our-insights/the-state-of-ai. Last accessed: 8 December 2025.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)