topic

jurisdiction

downloadable assets

article

Article

What makes supply chains resilient?

Supply chain resilience is the ability to keep production running when established suppliers or supply routes fail. Companies who care about supply chain resilience build flexibility into sourcing, logistics and who they partner with, to create alternative supplies fast when needed.

What happens to businesses when supply chains are disrupted?

When there are no alternative suppliers or supply routes, production simply stops. The key question is whether alternative supply is available. If a critical import is blocked — whether by sanctions, violent conflict or natural disasters — factories can fall idle until supply resumes.

Where local alternatives exist but remain undeveloped, companies must invest. This often requires authorisation from local governments, which takes time. In the meantime, companies need to increase working capital and build up costly safety stocks.

Even when local options are available, they may be more expensive or lower in quality, which can erode margins or competitiveness of the downstream product.

In short, supply chain disruptions are serious events that can significantly harm the business.

Examples:

- Severe weather or political instability in West Africa can disrupt cocoa supply. With no immediate alternative, prices can aggravate quickly and severely and chocolate factories may even sit idle.

- New government import controls on processed agri-commodities can require rapid investment in domestic processing capacity to comply.

- Switching to nearer milk suppliers may reduce supply risk, but quality may not meet the required level and costs may rise.

How do companies prepare for supply chain disruption?

There are several approaches:

- Diversify the supply base to avoid over-reliance on any one supplier. Even when alternatives exist, concentration can be risky: if a single supplier covers roughly 30–40% of a critical input, a disruption at that supplier can still halt production. Companies therefore aim to reduce such dependence. This includes diversified supply from several regions to reduce political and climate risks.

- Build your own local options. Firms may seek fast-track permits, or to create local capacity or develop local agricultural crops. A degree of self-sufficiency can insure against future shocks, though it may be costlier in the short term.

- Co-invest to create capacity and capability. Companies may partner with suppliers, investors—or even competitors—to accelerate new capacity (for example, a shared packaging facility or processing plant).

- Joint production and even joint R&D can strengthen resilience. Why R&D? R&D is often needed during re-shoring, when a globally sold product must be adapted to local materials, processes, or standards. To deter free-riding, companies that invest may wish to secure preferred access to the benefits of the investment, which must be structured with care.

- Pool purchases with other buyers to secure availability or negotiate better terms during shortages.

Each measure improves resilience but typically raises costs for the firm making the investment.

Where do competition law issues arise?

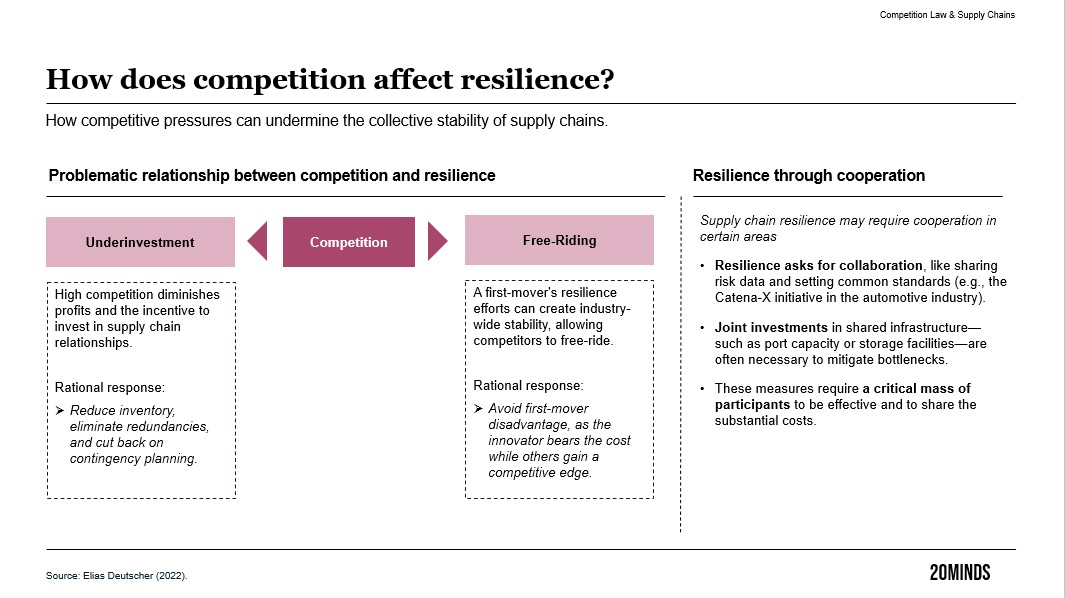

Collaboration, particularly between competitors, even when aimed at supply-chain resilience, sits uneasily with the free-market paradigm that underlies global competition laws, which relies on independent rivalry to deliver efficiency and lower prices.

Competition-law risks can particularly arise when cooperation goes beyond what appears necessary to secure supply. This may occur in vertical arrangements with suppliers and, often more sensitively, in horizontal collaborations with competitors.

How can firms minimise exposure to enforcement action?

Authorities are more receptive to cooperation that is clearly limited to addressing a specific supply risk.

Parties should consider the following steps to demonstrate compliance:

- As a general steer, parties should avoid forward-looking discussions of commercial strategy, such as future prices, margins, capacity plans, customer allocation or R&D pipelines, as these can be perceived as coordination on market conduct.

- Where joint purchasing is contemplated, coordination is typically ring-fenced to procurement steps only, with care taken to prevent any spill-over into downstream pricing or sales strategy.

- Information sharing is kept to what appears essential, preferably through clean teams and, where feasible, using aggregated or time-lagged data.

- If joint investments or JVs are proposed, they may trigger merger-control and/or investment screening reviews; then implementation should not proceed (to avoid “gun-jumping”) until the relevant clearances are obtained.

- Contractual devices such as most-favoured nation (MFN) or benchmarking clauses are often framed narrowly—tied to specific products, volumes and regions—and time-limited; broad or global parity terms can raise competition concerns. Exclusivity, where used, is typically limited in scope and duration so that viable alternatives remain available.

- Public support for localisation (for example, tax incentives or specific grants) may also attract separate scrutiny; the company may later have to comply with foreign subsidy related filing requirements. So, it is useful to record any government support received.

In short, cooperation to build resilience is often feasible, but it tends to be better received when it is targeted, proportionate, time-limited, well-governed and documented. The assessment is fact-specific and can vary by jurisdiction.

What practical approach should legal teams take when advising companies seeking to cooperate with peers?

In a disruption, speed often matters more than exhaustive detail.

Early on, legal teams add the most value by setting clear guardrails and a workable path forward for cooperation, rather than producing lengthy memos after the fact. Embedding legal counsel into the project team allows for the implementation of guardrails, enhances understanding of the business need and accelerates the provision of legal advice.

A concise playbook with three key steps can help:

First, define necessity and scope of the cooperation. Specify the problem being addressed, why cooperation is necessary, who needs to be involved, which activities are contemplated, the expected duration and how outcomes will be measured.

Second, limit information flow, ring-fence teams and set a time limit for the cooperation. Use clean teams where appropriate, restrict data to what seems essential, set a stop date with review checkpoints and document decision rights.

Third, record efficiency and consumer benefits. Keep contemporaneous notes and quantify effects (availability, lead times, quality and costs) to evidence necessity and proportionality.

The playbook should also set out what to watch out for:

- No forward-looking commercial coordination. Avoid discussions about future prices, margins, capacity, output or customer allocation; keep exchanges operational and risk-mitigation focused.

- Keep exclusivity and MFN/benchmarking narrow and time-bound. Tie any clauses to specific products, volumes and regions; avoid broad or open-ended parity terms.

- Handle governmental approvals before implementation. File any required merger-control, FDI, or subsidy control notifications and observe standstill obligations to avoid gun-jumping.

Example: Instead of drafting a full legal opinion, the legal team can promptly confirm that a joint purchasing arrangement appears permissible in principle for the stated objective, set communication boundaries (e.g., clean teams, no price/output discussions, minutes of meetings) and map the required filings and sequencing before any steps are taken.

What defines success in supply chain resilience?

Success means maintaining continuity without crossing legal lines: acting quickly, sharing risk in a responsible and proportionate way and keeping strategic decisions independent.

When companies plan early, document necessity and benefits and stay within simple guardrails, resilience tends to strengthen rather than strain compliance.

* Dirk Kessler is the General Counsel for Global Procurement and Secretary of the Board at Nestrade, Nestlé's company for the global procurement of commodities, ingredients, packaging, marketing, IT and corporate services.