topic

jurisdiction

article

Sample

Last year, Thierry Breton, European Commissioner for the Internal Market, reminded global technology companies that the Commission expects “technology in Europe to respect all of our rules on data protection, online safety and artificial intelligence". Accountability is important for markets to function, but could the EU’s hawkish regulatory approach prove to be too much of a good thing?

Yes, it could.

Essentially, we are witnessing an accumulation of liability for companies engaged in all types of digital activities within the EU.

Each of the recent EU digital acts affects the technology and data sector via a similar, but separate penalty regime. With the AI Act the EU adds another layer of regulation, and this layer happens to be extraordinarily complex, impacting not just large firms but any company using AI.

How does the EU’s liability regime for AI compare to its policies in other areas of tech regulation?

At first glance, the EU AI Act adheres to tradition, combining regulatory penalties with the possibility for customers or competitors to bring “follow-on” damage claims after a regulator finds a violation.

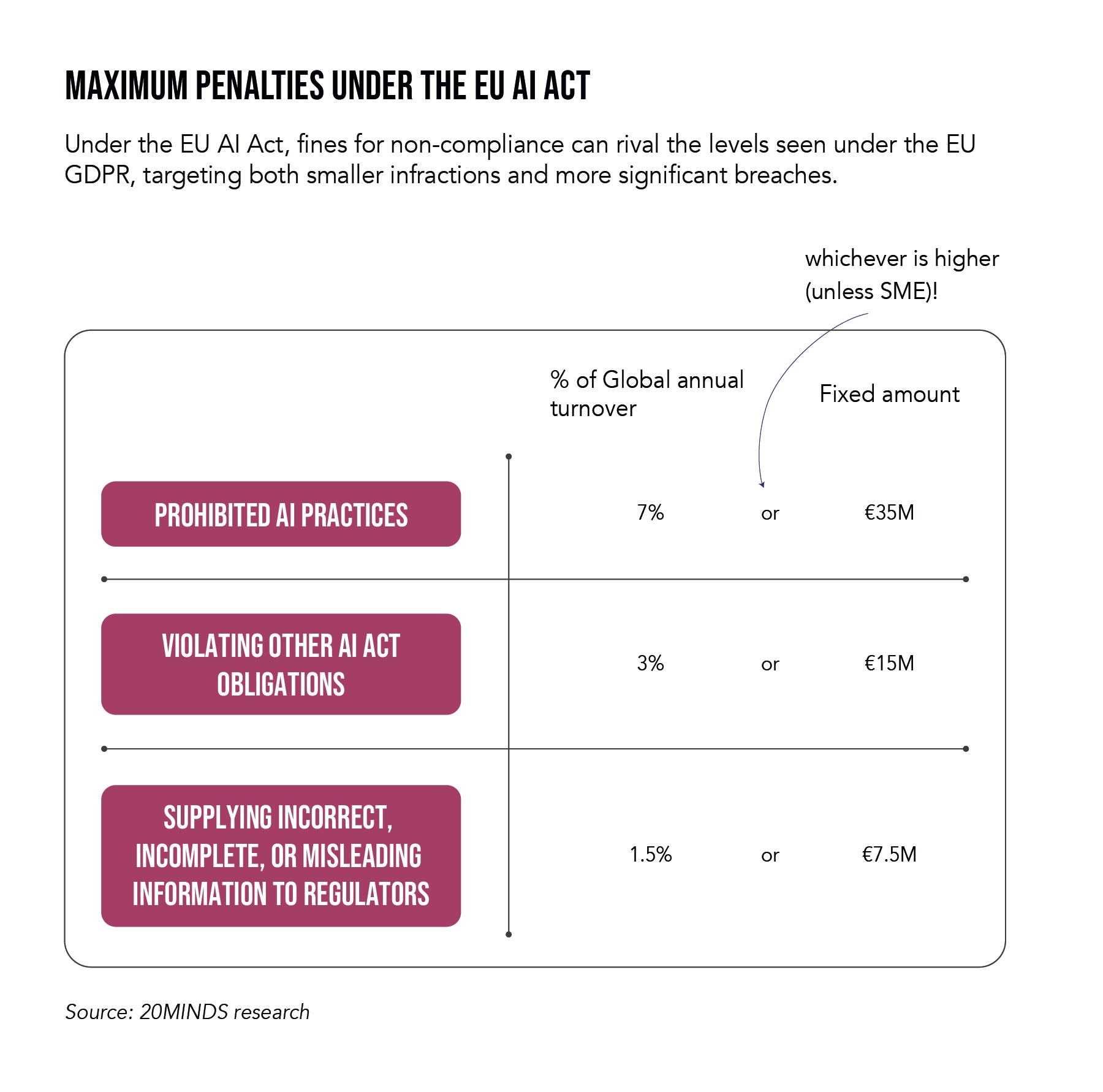

The regulatory fines could theoretically reach extreme amounts, as the cap is calculated based on global group revenues. We could be talking billions in the case of large global groups.

But at second glance, the Act stands out among other EU tech regulations due to its complexity. Passing the AI Act into law has proven to be one of the most extensive legislative processes Brussels has ever seen. These efforts have mostly gone into finding compromises and dealing with the emergence of LLMs. There’s been little focus on simplifying bulky articles and recitals, ironing out inconsistencies, governing the interactions with the GDPR and other EU Acts or resolving ambiguities. That’s a problem. The AI Act is extensively long and complex, includes many undefined terms and numerous cross-references within the regulation itself and to other EU laws. Companies will have to spend a lot of external and internal resources just to understand their obligations. The complexity also makes it harder to determine specific liability risks.

Does this mean that many companies do not yet understand how they will be exposed to fines under the EU AI Act?

Indeed, there is still a lot of uncertainty. We may see some companies doing too little here, and others too much there, because the legal requirements and AI use cases remain ambiguous. For example, if an AI deployer makes “substantial modifications” to the AI system by operating the AI system under their own name or brand, the deployer may be regarded as creating a new AI system. In this case or when using an AI System for new purposes, the company’s duties can increase from those of an AI system deployer to the much wider catalogue of the obligations of an AI system provider.

But what else can trigger this transformation? When does fine-tuning a third-party machine learning model or incorporating an existing AI system result in a new AI system, making the company an AI provider?

Clarity on these issues is crucial, but it will take a long time and numerous cases for us to achieve it; and the smaller the balance sheet, the less room a company has to absorb the cost of misdirected investments. Companies should urge the EU Commission to create more clarity by using its powers to issue guidelines and delegated legal acts.

The penalties for violations of the EU AI Act can be very high, even reaching into the billions. Who do you expect to be the primary targets for enforcement?

If the AI Act follows the path established by the GDPR, we will first see limited fines, and then, over time, the penalty amounts will escalate dramatically. Companies with high profiles in AI development or deployment are likely to become the first targets.

Firms already flagged for violating the EU’s other digital regulations will likely join them in the crosshairs, as this may indicate a pattern of non-compliance.

The EU AI Act does not displace the GDPR regime. Does that mean offending companies could be fined twice for the same violation?

To go a step further, violating the AI Act could in fact trigger the DPAs to take action. Why? Because DPAs may claim that a breach of the AI Act invalidates the legal basis for processing personal data, thereby making the act of processing illegal under the GDPR as well.

Companies will be the primary targets of enforcement. What about members of the board or management? Can they be personally held liable for fines?

There are no personal sanctions under the AI Act—generally, companies will be held liable—so regulators are unlikely to target board directors or members of management. Likewise, claims for damages will be directed primarily against companies. However, companies and investors might seek recourse if the company is exposed to fines or claims due to alleged wrongdoings.

Can shareholders be held liable for fines?

The EU aims to simplify the process of filing damage claims for harm caused by faulty or non-compliant AI systems. What is the reasoning behind this?

Humans make mistakes, including when they train or prompt algorithms to reduce human work. The potential liability exposure can be significant. Think of patients misdiagnosed by faulty AI, pedestrians injured by faulty autonomous driving systems or farmers whose harvests are ruined by malfunctioning automatic irrigation systems.

Crucially, if a company is found to have violated the AI Act, there will be a presumption that this violation led to any related damages. Lawyers representing alleged victims of malfunctioning AI will thus be highly motivated to file complaints with regulators, hoping to access files that establish clear AI Act violations.

What can investors do to minimise their exposure to fines and damages claims?

It’s primarily the company’s responsibility to ensure compliance with AI regulations. The AI Act imposes obligations on the operating company, not on investors or owners. Investors should set reasonable expectations for the companies they back—but what can investors reasonably expect from companies at this stage?

Although companies can certainly not ignore the AI Act, they may struggle to address everything at once. My advice is to start with the low-hanging fruit, with a few actionable steps and relevant processes:

- Establish a global AI Governance Framework: Defines responsible AI use within the organisation. Provides a legal foundation and defense against potential issues.

- Identify and categorise AI systems: Assess risk levels of all AI systems, including third-party services. Maintain comprehensive, up-to-date documentation.

- Prioritise customer-facing obligations: Be transparent about the use of AI in products/services. Provide clear notice when AI systems do not function as expected.

- Invest in resources for regulatory inquiries: Ensure prompt and accurate responses to inquiries. This is critical for companies heavily reliant on AI to avoid penalties.

- Reuse existing resources where possible: The AI Act is a cross-over between digital, data, consumer protection and product safety regulations. Where possible, companies should redeploy or modify existing processes and structures to ensure compliance.

The quality and robustness of a compliance system make a difference over the long term. Companies already successfully operating GDPR-compliant systems, ideally including privacy-by-design elements, will enjoy a head start as existing compliance systems can be adapted to comply with the AI Act. Considering the procedural end is crucial, particularly in preparing for the final stages of a defence process, like handling legal issues or resolving disputes. This involves strategically anticipating and preparing for potential complaints, investigations, and responses to fines or penalties. The process often requires a bit of reverse engineering, where one starts by considering the possible legal defences that might be necessary during regulatory proceedings or in court. From there, one works backwards to strengthen these defences in advance, ensuring readiness to counteract any challenges or accusations effectively.

Tim Wybitul is partner and Chair of the Data Privacy Committee at Latham & Watkins.