topic

jurisdiction

downloadable assets

article

Sample

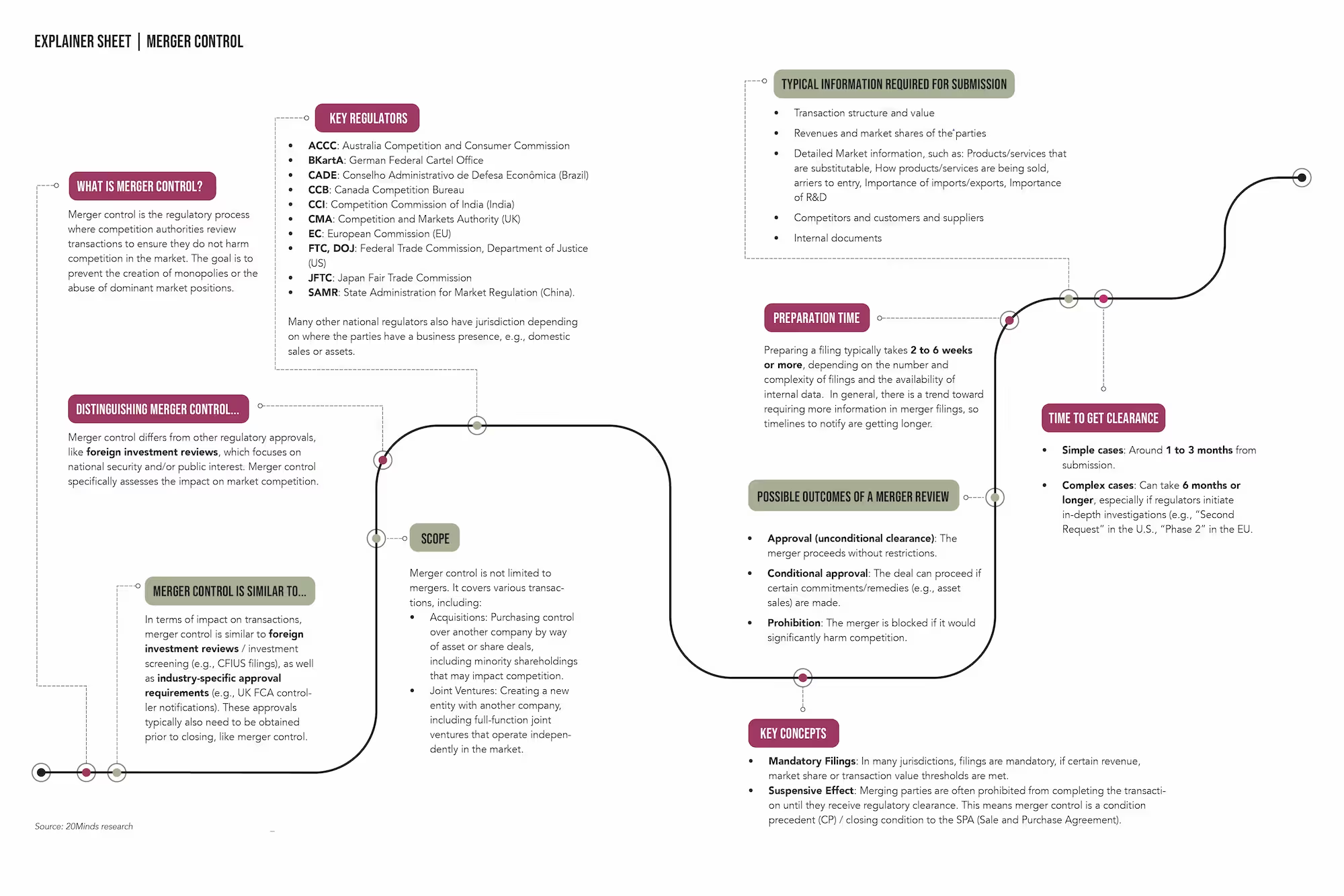

Larger M&A deals can trigger numerous regulatory filings across the globe. Most of these filings relate to merger control. Preparing merger filings can be resource intensive. Yet, the use of project management techniques and cloud storage resources may provide new opportunities to collect information earlier and more efficiently. In this discussion, Gil Ohana shares practical insights on managing merger control work within a company.

Number of filings

Twenty years ago, M&A deals typically needed to be filed in only a few jurisdictions, with the U.S., Canada, and Germany being the most common. What has changed since then?

Gil: Today, transactions (mergers and acquisitions, but also the formation of some joint ventures) may trigger filings in dozens of countries if the buyer and seller have a broad international presence. Enforcement agencies sometimes take an expansive view of what constitutes “presence,” and filings can be required because of factors such as revenue, assets, or even just the ability of either party to compete on the domestic market. In industries like consumer-packaged goods, where products are sold in numerous countries, having to prepare 50 to 60 notifications for a single deal is not unknown. Larger transactions in the technology sector often require notifications in more than a dozen jurisdictions.

This increase in filings over the years is largely due to the increasing adoption of merger control regimes. Under these regimes, if specific thresholds—most often based on the annual revenue of the acquirer and target worldwide and in the relevant jurisdiction—are met, the merging parties must notify. There are a few large jurisdictions, including the UK and Australia, where notification is nominally voluntary, though Australia has announced that it is moving to mandatory notification possibly as early as 2025.

Increasingly, national merger control regimes have become suspensory, meaning that approval is required before the parties can combine operations, at least in that country. For example, Brazil moved to suspensory merger control in 2011.

How has the increasing number of merger control regimes globally impacted companies’ M&A ambitions?

Gil: The proliferation of merger control regimes has definitely impacted the M&A landscape. Companies now have to think carefully about how the need to obtain multiple approvals may affect their deals, both as to substance and timing. For example, they might decide to forego certain control rights to avoid notifications in certain countries. It also means deals can take longer to close because of the extra time needed to get approvals from multiple regulators. And sometimes, the risk of a deal being blocked or being approved subject to burdensome conditions is just too high, so companies might decide not to proceed with an acquisition or to try to address anticipated competition issues proactively, for example by divesting an overlapping business.

“Making a call” on whether to file

Companies often assess the risk of not notifying, and may on occasion decide to take the risk of not filing even if a filing is technically required, for example where the domestic business in the relevant jurisdiction is very small.

Gil: In most countries with mandatory merger regimes, if a notification is triggered, companies are advised to file. However, if a company has minimal presence in a country but still crosses the relevant threshold, it may assess the risk of not notifying.

In that assessment, companies consider a number of complex factors, including: How onerous is the notification process? How do the timelines fit with other regulatory approvals the deal will require? What is the reputation of the competition enforcement agency for transparency and predictability ? What are the potential consequences of not filing? Are penalties for not notifying limited to fines? How frequently has the regulator imposed penalties in the past? Is the regime suspensory? What are the merging parties’ respective turnovers or physical presences in the country and how do they expect those to change in future?

Political factors and the risk of complaints from customers, competitors, or suppliers must also be considered. Sometimes, companies file despite limited local activity to maintain positive relationships with the government.

Companies considering whether to notify in particular jurisdictions may ask the law firm they select as global coordinating counsel to relay, on a no-names basis, what similarly situated merging parties have decided with respect to particular jurisdictions, and otherwise to score the risk of not notifying. Ultimately, this is a risk-based decision for clients to make and there is often not a clear right answer.

The decision whether to include a particular jurisdiction arises when the merging parties negotiate over a list of regulatory approvals that will be conditions to closing. Sellers generally want as few closing conditions as possible, in particular where the seller will not survive the completion of the transaction. Buyers, conversely, generally seek to minimize post-closing risks and uncertainties by seeking to identify all potentially applicable merger control requirements, even if the result is more numerous filings. The merging parties’ decision whether to include (or not) a particular jurisdiction as one where approval is required before the deal can close may need to be made under significant time pressure as the parties push to get a deal signed.

Managing the workload

Preparing antitrust filings, particularly in more complex cases, involves collecting and assessing a myriad of information and documents. Who within the company can help manage the merger control workstream?

Gil: The default answer is the legal staff, in particular specialist competition counsel if the company’s legal function includes them, who can act as a key point of contact and information collection. Appointing a dedicated internal person or team to coordinate information gathering and written submissions to ensure consistency across jurisdictions can significantly streamline the process, reduce errors, and avoid inconsistent data being used in different jurisdictions or inconsistent arguments being made to different enforcement agencies reviewing the same deal.

Some companies have project management teams that specialize in organizing complex initiatives. If such a team exists, it may be helpful to leverage their expertise. They often are familiar with the use of Gantt charts and other project management tools used to track interdependent deliverables. That can help add structure to the management of the regulatory response efforts, helping to ensure that timelines for anticipated filings are met.

There’s a common perception that once the deal is announced, the deal team can take a break. However, that's when the antitrust work really begins!

Gil: Exactly. For the internal antitrust team and their advisors, deal announcement is closer to the beginning of the timeline than the end. When I was in-house, I sometimes reminded the deal team that “crunch time” for the regulatory process would start just when they most wanted to relax, after they survived the sprint to get a merger agreement signed. Once a deal is public, the antitrust team has access to a wider set of knowledgeable business people. It also typically means wider access to data sources, for example finance data and sales opportunity data.

Few of the product management, finance, and sales resources that you need help from have “obtain regulatory approvals for the deal my company just announced that I was not previously aware of” in their job descriptions. So it’s critical for management to make individuals and resources available to support the preparation of merger notifications on time.

Speeding up the process

Lengthy filing preparations can delay the transaction. How can we speed up the process?

Gil: First, try to gather as much key information before announcement, to the extent possible given confidentiality constraints. Once a deal is public, start contacting people who were not aware of the deal to begin interviews and data collection processes, involving external counsel and an economic consulting firm if one is engaged. Companies that do frequent deals may benefit from regularly mapping out key information sources and relevant data sets.

Second, if internal information security policies permit, consider whether to have internal teams upload requested data and documents to a secure shared site, allowing external consultants direct access. This will reduce, though rarely eliminate, one-off questions (“what was the gross margin from sales of spherical widgets in Ruritania in FY 20XX?”). That can help preserve good relations with businesspeople whose ongoing cooperation you will rely upon for months, maybe a year or more.

Third, be conscious of the cumulative burdens on internal stakeholders. Information requests often target the same small group, such as the finance team. Consider creating some kind of clearing-house function so that similar requests are consolidated. And ensure timelines are realistic—a one-day turnaround might seem feasible for a particular request, but not when the recipient is responding to 15 similar requests simultaneously.

Frontloading work

Is it advisable to frontload work, for example, by gathering information that has not yet been requested by the regulator?

Gil: This is a common question from clients: Should we incur the cost of proactively collecting information if doing so will help us avoid delays later?

I wish there was a single right answer. But the decision inevitably requires balancing potential time savings against the risk of wasting resources or having to redo work later.

A good example is whether to gather documents from individuals to anticipate a Second Request in a U.S. merger review. The DOJ Antitrust Division or FTC decide to issue Second Requests when they want more detailed information to assess the antitrust implications of a transaction. This usually happens 30 or 60 days after the initial HSR filing. It’s hard to capture how broad second requests can be. The image I have used with clients is to imagine that an agency sticks a very large vacuum cleaner through the roof of your corporate headquarters. Responses can consist of millions of documents and terabytes of data, as well as detailed narrative answers that require extensive involvement of businesspeople.

Given the time required to respond to a Second Request, clients sometimes consider whether to pre-pull custodial datasets. Doing so can be very costly. Depending on the company’s IT infrastructure, the response can strain internal computer and storage resources. And merging parties are rarely sure that a Second Request will issue, nor can they anticipate perfectly what product areas the DOJ or FTC will be interested in.

However, if the merging parties attach a high value to getting through the US regulatory process as quickly as possible, frontloading document collection and other tasks is something they should consider.

Unannounced transactions

How do you run the merger review workstream before a transaction is announced?

Gil: One challenge in assessing merger risk is the small number of knowledgeable businesspeople who are aware of a potential deal before announcement. Deal teams are concerned about leaks and seek to minimize the number of people who are aware of the proposed transaction. The lack of access to knowledgeable people and the relevant information they could provide can make the risk assessment less precise. You advise businesspeople regarding important decisions based on limited information, which can be scary: The clients you support need to take crucial decisions about whether to proceed with a transaction on the basis of a competition risk analysis that is necessarily based on incomplete information.

One helpful development is the increased use of cloud storage for email and other internal documents. The ability to access documents created by employees who are not yet aware of a deal can give advisers a preview of what an agency is going to learn when they investigate. Cloud data repositories like Office365 or GoogleDocs may permit you to access datasets and run queries that will help you review strategy documents and sales information. There can be data privacy issues or other sensitivities in this area that you will want to keep in mind.

External communication

Statements, oral or written, from company reps about the deal and its rationale are not always helpful during antitrust reviews. You have worked on deals that faced significant regulatory scrutiny. How should companies approach external communications for transactions that are high-profile?

Gil: Start by identifying core themes early and build your communication strategy around them. It is important to manage communication in a way that aligns with your company’s culture. For example, for companies with more public-facing personas, a blackout on communication is unrealistic.

Once the themes are established, stay consistent, but tailor messaging to suit different audiences. It helps to be sensitive to the balance between thematic consistency and the knowledge company representatives have about the audiences they regularly touch.

Assume that regulators are closely monitoring all public statements. Pay attention to all communication platforms, including social media, YouTube, etc. Employees may feel empowered to post on their own, which can complicate the effort to maintain homogenous messaging.

What are the key steps to successfully implementing a communications strategy in the context of merger control?

- First, involve communication professionals as early as possible, subject to the point above about keeping deal teams small.

- Second, consider putting in place targeted competition law guidance or training to the teams involved, with a focus on the core themes and how they can be elaborated for specific audiences.

- Third, have a core group review and approve all public statements and counsel on internal messaging. This helps maintain control over messaging, despite the need to address varied audiences such as specialist competition media, the general press, or trade publications covering the merging businesses.

- Fourth, ensure that buyer and seller coordinate closely and include provisions regarding the extent of cooperation in the agreement. The buyer will generally take the lead, but the seller will have stakeholders (for example, employees, existing customers, shareholders and investors) that it will need to communicate with when a deal is announced. Some of those stakeholders may subsequently be contacted as part of agency investigations.

Merger control and geopolitics

Have merger control cases become more political?

Gil: I don’t think merger control reviews have generally become politicised. Agencies decide whether to let deals go forward, or not, based on the merits as they see them. But there is an increasing incidence of what I would call “soft FDI” concerns. For example, concerns about a national champion being acquired by a foreign company, or an off-shore merger creating a national champion that threatens a local firm. In a world where globalization seems to be waning, that kind of concern will likely increase.

For the small percentage of deals raising that kind of concern, it’s critical to be alert to potential political reactions and put together the best possible team. I would recommend the following steps:

- First, assess the parties’ relationships with the governments in various countries where concerns may emerge. This includes government contracts, previous state funding, or involvement with technology or resources that may be seen as important to the national interest.

- Second, identify people inside and outside the company that can help with the (geo-)political angle. This is rarely purely a legal matter—government affairs teams and external advisors may be crucial in planning adequately. Internal teams may have valuable relationships and insights, and external advisors can complement the internal team.

- Third, understand who is doing what. It’s not a good look when a law firm in a particular country is seeking a meeting with the same government official that the company’s head of government affairs in the country met with last week. The key is aligning everyone to ensure a smooth process.

Gil Ohana is a counsel at Davis Polk and previously served as Senior Director of Antitrust & Competition at Cisco Systems for 15 years.