topic

jurisdiction

downloadable assets

article

Sample

What are those “non-traditional” M&A risks and why are they moving to the fore?

Companies involved in M&A today face legal and regulatory risks that were not front and centre a decade ago.

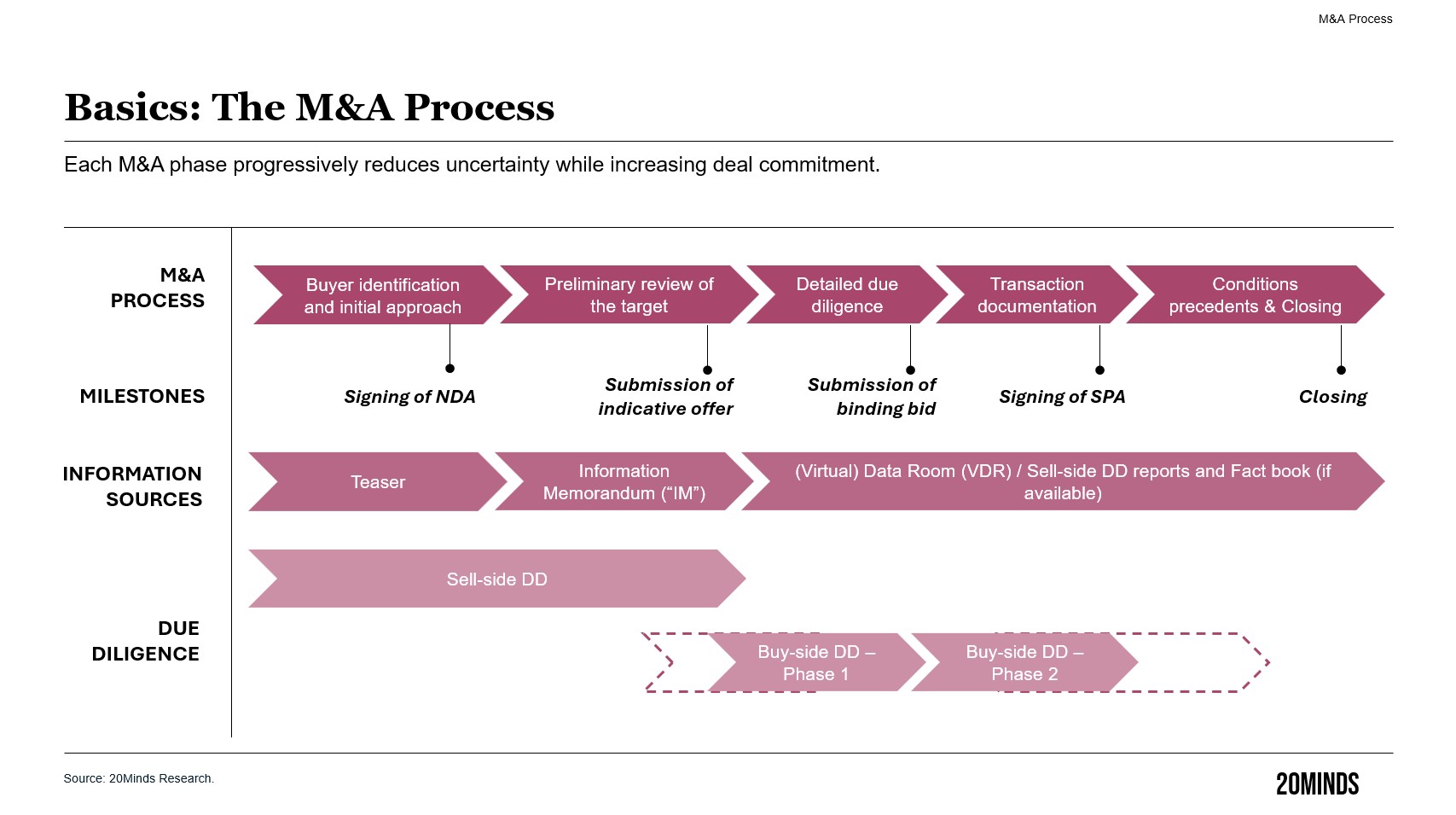

Until recently, M&A risk analysis focused largely on approval risks arising from merger control, typically limited to transactions in highly concentrated markets.

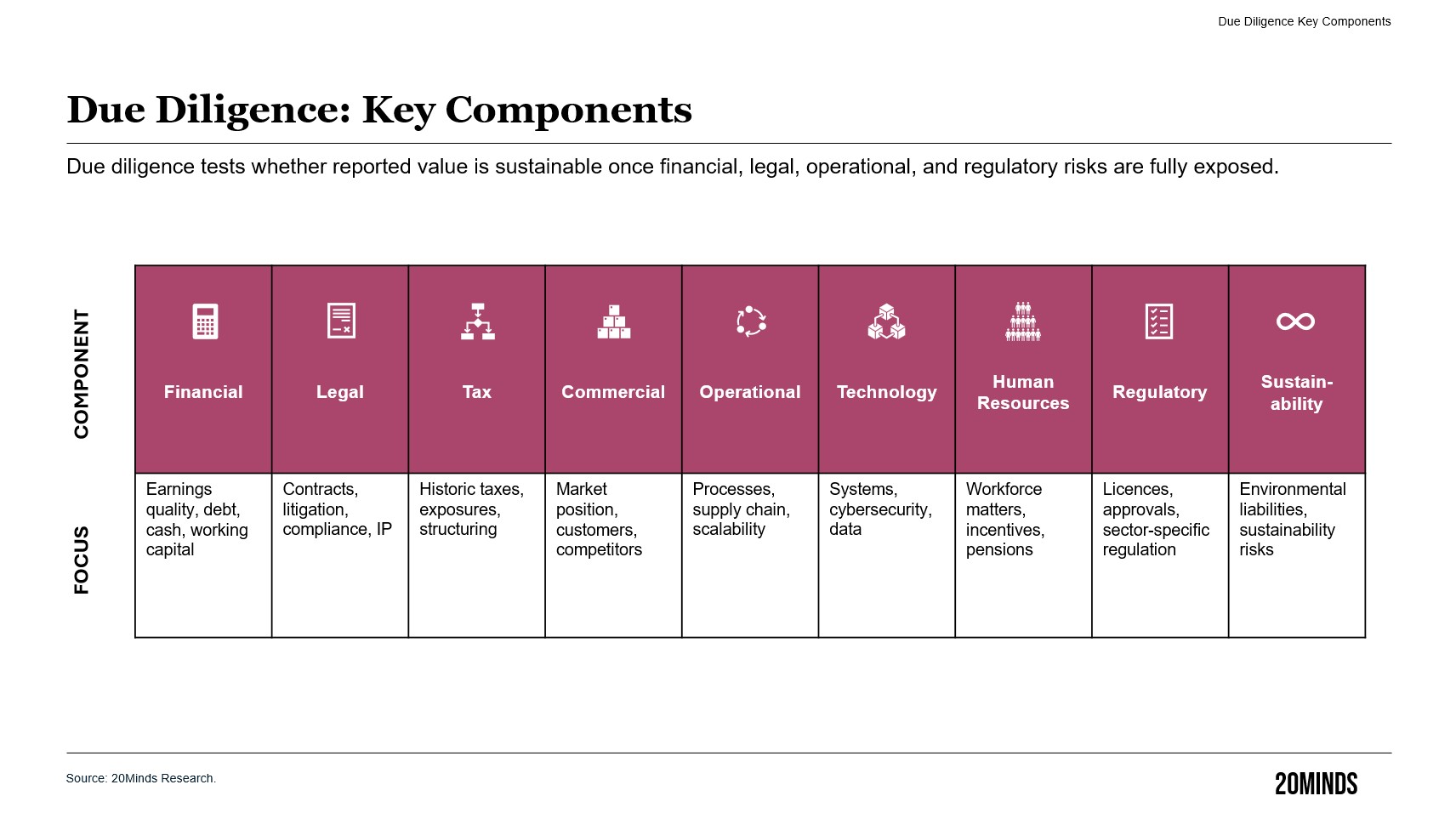

Legal due diligence was relatively standardised and slow-moving, covering familiar areas such as legal title, employment, pension matters or anti-bribery and corruption. The M&A process felt settled.

That picture has changed. Acquirers now have to contend with a surge in regulatory risks that arise from new policy concerns:

- Investment screening or “CFIUS-style” regimes have expanded from a handful in the beginning of the century to more than 30 active jurisdictions. These regimes are mostly pre-approval systems, meaning transactions generally cannot close until national security concerns have been resolved. The scope of these reviews has widened, now covering issues such as the integrity of citizens’ data or the know-how of domestic companies, security of supply chains and access to critical inputs and infrastructure.

- Industrial policy has re-emerged in a different fashion. These concerns can go beyond what national security alone requires and are increasingly strategic in nature, focusing on competitiveness, independence and overall economic well-being. They are no longer limited to protecting so-called “national champions”, i.e. companies that governments regard as strategically important to the national economy or security. Governments increasingly go to the enablers of competitiveness and view access to data and computing power, for example, as matters of economic independence and, ultimately, sovereignty.

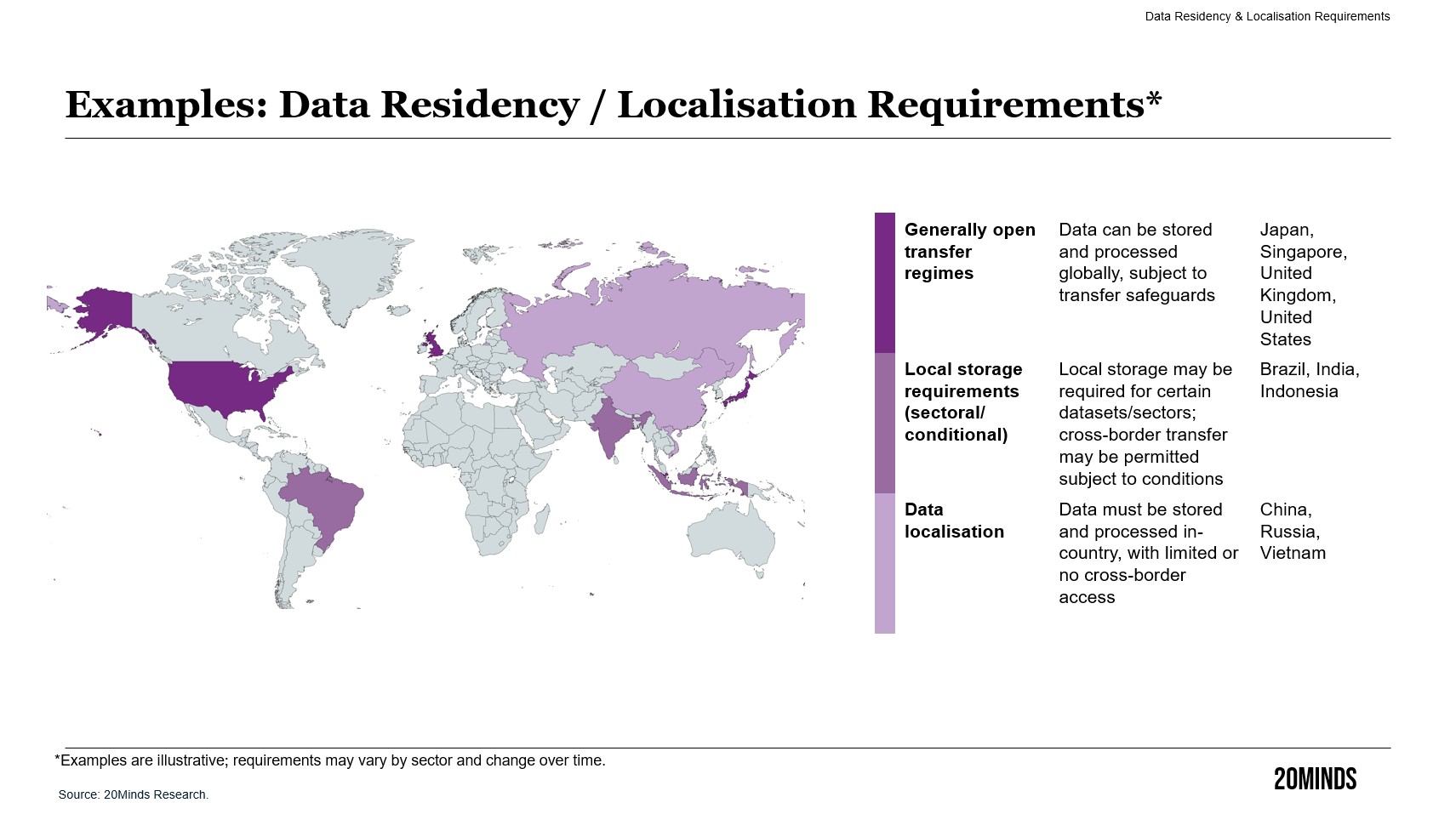

- Data localisation or residency requirements now exist in more than 30 countries. The overall number continues to grow with many taking the form of sector-specific or conditional limitations, driven by national security concerns, privacy considerations and industrial policy objectives (e.g., treating data as a strategic asset).

- Sustainability-related diligence and disclosure expectations have increased and can add time, cost and reputational scrutiny to a deal. However, in most transactions this may not translate into a true closing risk unless it is tied to a specific legal requirement, enforcement action, financing condition or a clear value-impact issue (e.g., material litigation, regulatory breach or loss of key customers/investors).

In short, issues once considered peripheral, such as where data is stored, who controls computing resources or how credible sustainability claims are, can now materially affect transaction risk. They introduce new reasons why a deal may be delayed, blocked or abandoned.

Let us start with data residency requirements: why do they matter in M&A?

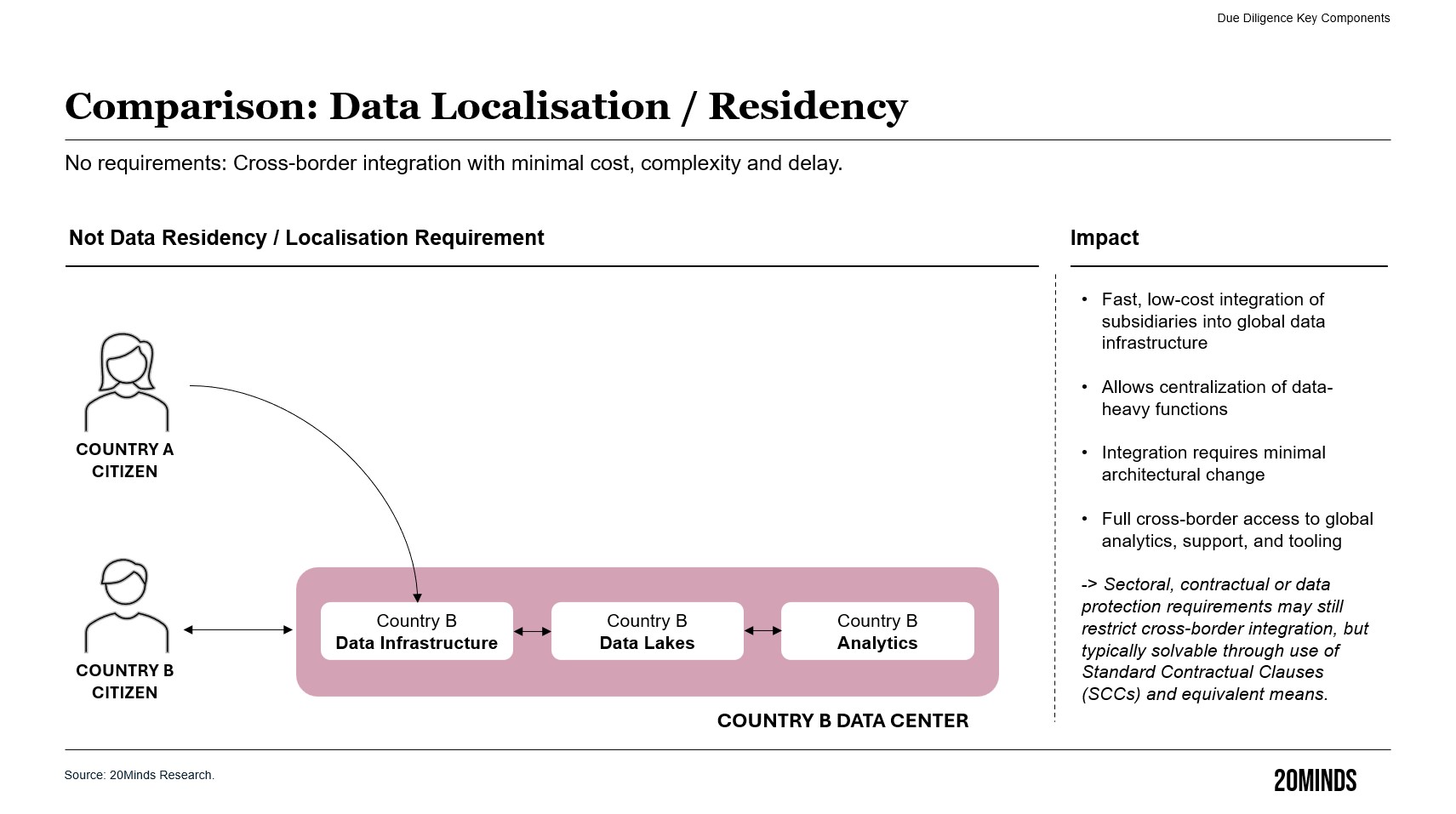

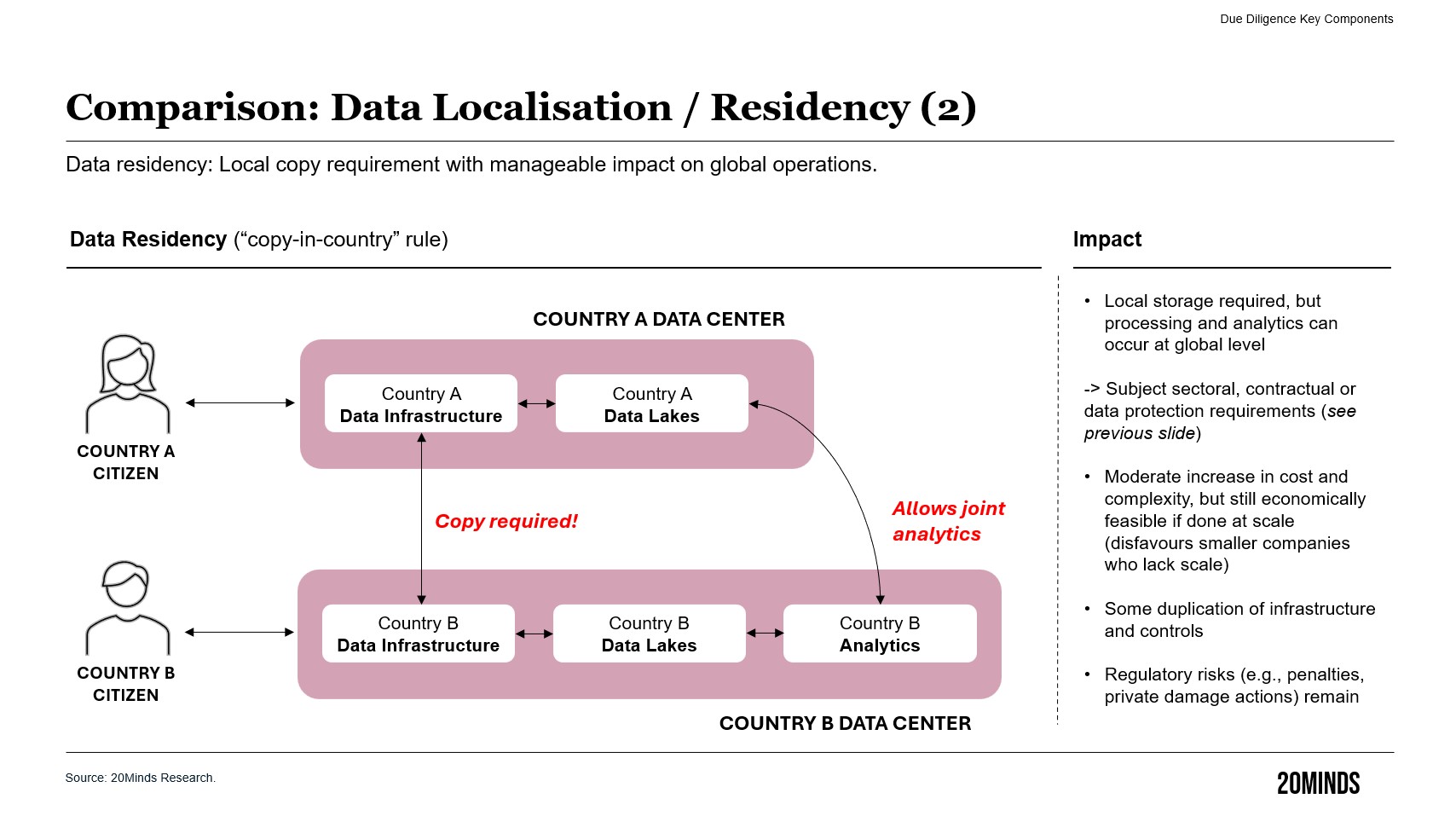

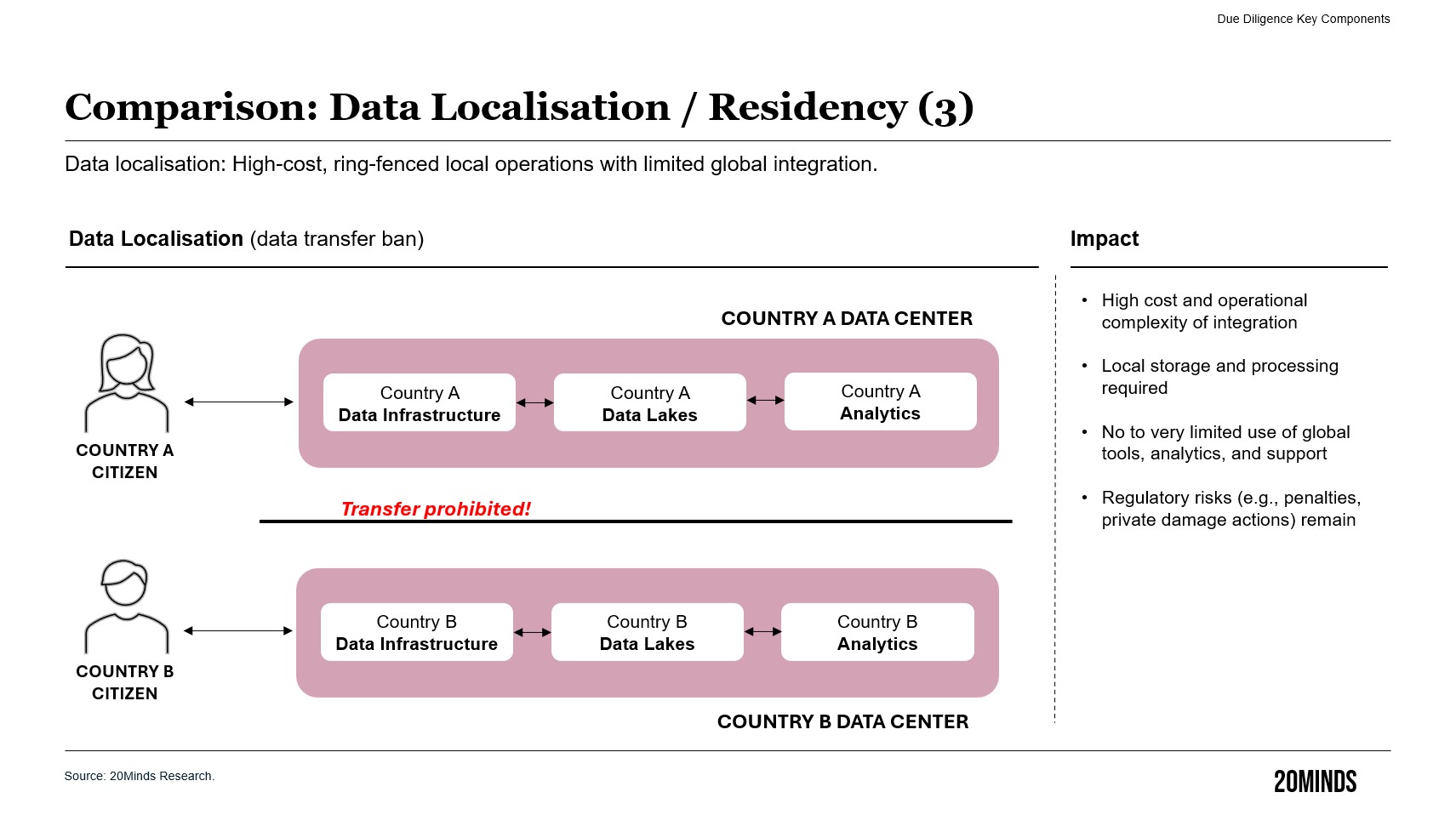

Data residency and localisation laws require certain categories of data to remain within national borders. Two main models exist:

- First, copy-in-country rules: a local copy of the data must be stored on servers within the jurisdiction (for example, under some financial services or health data regimes).

- Second, export bans: specified data cannot be transferred abroad or stored on foreign servers at all.

Some countries, such as China and Russia, have had these requirements in place for longer. Others, including fast-growing economies like India and Indonesia, are introducing sector-specific or conditional limitations which can still affect cross-border operating frameworks.

This trend is primarily driven by public-policy choices rather than optimal operational design. From an enterprise perspective, integrated and secure global data infrastructure is critical to efficiency, innovation and safety. Companies therefore need a clear understanding of regulatory limitations while preserving the well-established benefits of global integration.

For M&A transactions, this has direct and practical implications:

- Transaction risk: authorities may question whether foreign ownership could expose sensitive datasets to external access or control and employ investment review powers to intervene in the transaction.

- Operational fragmentation: localisation rules can fragment data assets, leading to duplicated storage and analytics costs and limiting centralisation of data-reliant functions (e.g., HR, customer care).

- Joint ventures: parties must determine who owns or controls the data, what can legally be transferred and how derivative datasets are treated.

These constraints can directly affect valuation. Expected synergies may not materialise if data cannot be integrated and instead must be duplicated or ring-fenced on local servers. They can also complicate post-closing integration, for example where customer or employee data cannot be shared with a foreign acquirer. Importantly, these issues may persist through to exit, affecting the future sale price of the business.

Data localisation risks are also difficult to mitigate. They typically arise from public-interest legislation, meaning that they cannot be contracted out of easily. Enforcement risks are not only financial in nature (e.g., fines) but may also include orders to suspend data transfers, require local storage or processing or mandate the segregation of systems.

As a result, in many cases the only practical response is to anticipate these risks early and allocate them clearly, so that the buyer does not end up bearing all of the costs and exposure.

Not only data itself, but also the infrastructure that stores and processes it is increasingly viewed as a critical asset.

Computing power and cloud storage capacity underpin modern productivity growth. Governments therefore have a strong interest in ensuring that domestic industries retain access to these resources. In response, they are deploying a range of measures to secure access to what they see as critical inputs: data centres, semiconductors and the energy on which those data centres depend.

This government interest is visible across jurisdictions:

- In the EU and the United States, the respective Chips Acts are designed to boost domestic semiconductor manufacturing, research and workforce development.

- U.S. export controls introduced in 2023–24 restrict the sale of advanced AI chips to China.

- China has reportedly required chipmakers to use at least 50 per cent domestically manufactured equipment when adding new capacity, as part of its push to build a self-sufficient semiconductor supply chain.1

- National foreign investment screening regimes increasingly include cloud services and data centres within their scope.

By way of example, the United Kingdom’s mandatory notification regime under the National Security and Investment Act lists “data infrastructure” as one of 17 sensitive sectors.2 In Australia, a foreign person must obtain prior foreign investment approval before starting a business or acquiring a direct interest in a data centre or cloud service provider that stores, or has access to, certain categories of data.3

Competition regulators have also started to view compute capacity as a potential source of market power. For example, the OECD’s 2024 report flags “potential competition issues” arising from vertical relationships involving “computing power.” This includes scenarios where a firm has market power in key computing hardware or cloud services while also competing downstream in foundation models.4 Similarly, the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) has stated that a small number of incumbents hold strong positions in foundation model development through control of “critical inputs like compute” and has warned that firms controlling such inputs may restrict access in order to shield themselves from competition.5

Transactions involving compute, or its enablers, may attract dual scrutiny:

• Investment screenings, where control of critical inputs and infrastructure may shift to foreign ownership.

• Merger control reviews, where a transaction could reduce rivals’ access to computing capacity or related inputs.

Sustainability has also muscled its way onto the policy agenda, where it had been far less visible in the past.

Sustainability-related concerns do not typically affect deal certainty, as there is currently no standalone approval requirement linked to sustainability. But they are not merely reputational either.

Where a target has been involved in green-washing, the acquirer may inherit significant post-closing exposure, including from investigations by competition regulators (e.g., the UK CMA). These investigations can result in fines, civil litigation risks and reputational damage.

Moreover, a merger control strategy may rely on an ESG-related rationale. This may be used to support arguments on market definition, efficiencies or the suitability of remedies. In such cases, any information provided to authorities about sustainability should be evidence-based. It should also be internally consistent. This helps avoid penalties.

Traditional legal and financial due diligence relies on relatively clear evidence standards. By contrast, sustainability-related due diligence often depends on self-reported information with inconsistent metrics. If environmental or climate-related claims prove overstated, the target may lose access to “green” financing or face enforcement action after closing.

How can corporate teams adapt?

I do not think that those non-traditional risks should be managed through enhanced due diligence alone. Instead, I would recommend a few risk management steps:

First, transaction heat maps: Frequent acquirers may benefit from developing jurisdictional dashboards that show, for example:

- where data must remain onshore;

- which countries treat cloud, data centre, or semiconductor assets as sensitive assets;

- the thresholds that trigger competition or national security reviews; or

- where enforcement against misleading green claims is most active.

These heat maps help internal teams identify risks early, before engaging external counsel or committing to deal terms.

Second, scenario planning: Scenario planning helps teams anticipate shifts in regulatory posture and identify appropriate responses. Because exit risks directly affect valuation, exit scenario planning should already be undertaken at the initial acquisition stage.

Third, organisational preparedness: Companies should also invest in identifying and addressing potential issues early in the transaction process.

- Legal teams conducting due diligence and negotiating transaction documents should, where possible, coordinate with policy and regulatory affairs teams that engage with governments on a day-to-day basis. This helps ensure that the transaction aligns with the company’s broader engagement strategy and public positioning.

- It may be useful to prepare evidence showing how the transaction contributes to objectives such as technological resilience or sustainability and to document safeguards addressing specific concerns upfront.

Sources

1 Exclusive: China Mandates 50% Domestic Equipment Rule for Chipmakers, Sources Say.” Reuters, 31 Dec. 2025, www.reuters.com/world/china/china-mandates-50-domestic-equipment-rule-chipmakers-sources-say-2025-12-30/.

4 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Artificial Intelligence, Data and Competition. OECD Artificial Intelligence Papers No. 18, OECD Publishing, 2024. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2024/05/artificial-intelligence-data-and-competition_9d0ac766/e7e88884-en.pdf.

5 https://www.gov.uk/government/news/cma-outlines-growing-concerns-in-markets-for-ai-foundation-models.